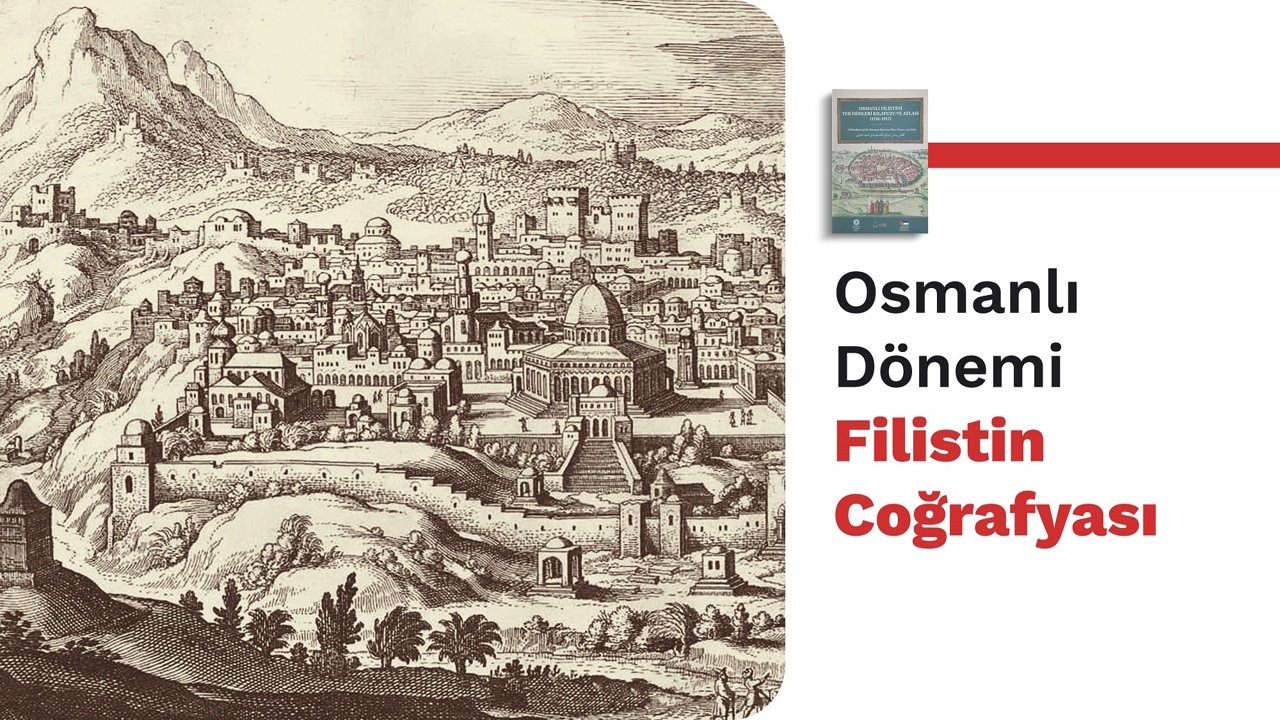

Palestine in Ottoman Times

Pazartesi, Şubat 5, 2024

Palestine in Ottoman Times

Palestine was the name of the coastal part situated between Jaffa and Gaza back in ancient times. However, once the ancient Greeks started referring to it for the inlands, too, the word Palestine then stood for both territories ranging from the coast to Arabian Sahra. For sure, the word Palestine was passed down from the Greeks to the Romans and the Byzantines. The reference was passed down to the Muslims, as the Caliph Umar b. al-Khattab included the word ‘Palestine’ for the central part of the country in his two treaties with the inhabitants of Iliya and Lid. Later, Islamic states referred to this word as an administrative term for the southern part of Palestine and part of Jordan under the mandate established in the 20th century.

Throughout history, the boundaries of this geographical concept have expanded and contracted, and there has never been a complete consensus over it. However, in any case, the word ‘Palestine’ has always been the common term for the territory between the Mediterranean Sea to the west and the Jordan River and the Dead Sea to the east. This term was preserved during the centuries-long Ottoman rule, which played a major role in the history of Palestine. It’s possible to see it in the bodies of Ottoman artifacts and travel diaries. Authored by Kâtib Çelebi in the first half of the 17th century, Kitâb-ı Cihannümâ (Book of World’s Image) features two maps of Palestine. The first map focuses on the Mediterranean, showing Damascus and Palestine, named as “Land of Palestine”. This is probably the first time Palestine was mentioned in an Ottoman map. On the other hand, the second map was drawn under the title of “İklim-i Ceziretu’l-Arab” (Geography of the Arabian Peninsula). This shows a clearer delimitation of Palestine. The descriptions accompanying the maps note that the borders of Palestine extended from Gaza and Jerusalem Liwas in the southwest to the Sinai Desert, between the Mediterranean Sea and Arish. The Dead Sea and the Jordan River are situated in the southeast. The border stretches into Caesarea through the Jordan River in the north. Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi, a local, described Palestine as follows in the 18th century: ‘Palestine is located longitudinally from Rafah to Leccun and latitudinally from Jaffa to Jericho.’

In an early 19th-century Ottoman map of Palestine, the borders of Palestine are drawn along with Damascus and displayed as the territory that straddles Ottoman Asia and Ottoman Africa. The administrative structure of the Ottoman rule did not allow for a clear delineation of the borders of Palestine. This is because this territory was a natural part of Syria under the centuries-long Ottoman rule. As there was no border to detach it from Syria, no environmental, racial, and historical barriers existed to do so. That is why Palestine was always part of Biladüşşam (Greater Syria) provinces except for during the tenure of an Ottoman governor when Jerusalem directly reported to Istanbul. Ottoman literature progressed accordingly.

Palestine had been shown as part of Syria in any history or geography book that preceded World War I. The Ottoman government unified the provinces of Jerusalem, Acre, and Nablus under the umbrella of Acre in 1831 in the face of the risk posed by Mehmed Ali Pasha’s Dynasty of avarice. Mehmed Ali Pasha’s brief rule in Syria gave rise to European interventions. As a result, the Ottoman Empire took new positions in the face of the interventions. During Mehmed Ali Pasha's rule over Syria, new administrative arrangements came to life and the land of Palestine became more distinct for the Ottomans. Sultan Abdülmecid offered a series of proposals to Mehmed Ali Pasha, seeking to reach an agreement at a time when the disagreement between the central and local administrations remained in effect. The proposals called for handing over the administration of Acre and South Syria to Mehmed Ali Pasha to rule for life. The borders of the territory, which Sultan Abdülmecid offered to Mehmed Ali Pasha to rule, extended from Re's Nafûra to the Mediterranean coast, as well as from the northernmost to the location where the Sisban River flows into Lake Tiberias, streaming through the western shores of the lake and including the embankment of the Jordan River and the west of the Dead Sea. A straight line from here would end up in the Red Sea and the northern part of the Gulf of Aqaba. This line would go through the western part of the Gulf of Aqaba and the eastern part of the Gulf of Suez, making its way to the city of Suez. However, the proposal could not enter into force once Mehmed Ali Pasha failed to agree on the terms of the Sultan in due time.

The Ottoman Empire went on its way to set the proposed borders in 1872 and established a province independent from Bilad al-Sham. This new province covered Acre, Nablus, and Jerusalem. The northern border of this new province extended to the line separating Acre and Beirut and covered all Jewish and Christian holy sites. (Such as Safed, Tiberia, Nazareth, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Hebron). However, the Ottoman government soon realized the drawbacks of keeping these territories together within the body of the same province and went on to abolish it. In fact, a new development unfolded the same year. The Governor’s Office of Jerusalem, which had reported to Istanbul through the province of Syria, was administratively affiliated directly with Istanbul. Analyzing the matter, Shultz argues that this new practice was a middle ground against the pressure of the European states, which were opposed to the concentration of all holy sites in one single province. Butrus Abu Mennah, on the other hand, considers this development as a precautionary measure against the possibility of the Mehmed Ali Pasha dynasty growing greedy and taking the region back under his control. It is noteworthy that this new administrative measure came after the submission of a report by Abdüllatif Suphi Pasha, Governor of Syria, to the government. He saw the role that the Europeans played in the bloody events in Damascus and Beirut and the developments that followed, and he warned the government about the future of foreign operations across this land. That is probably why the state introduced new regulations to secure these delicate sites and put a stop to European interventions. Whatever the motive was, from then on Jerusalem became the hub of the central and southern lands, and the districts of Gaza and Jaffa were permanently attached to it.

Sometimes the district of Nablus and, from 1906 and 1909, the district of Nazareth, which was part of the Province of Acre, were also affiliated to Jerusalem. For sure, this reinforced the position of the territory to grow into an administrative zone independent from the neighbors. It seems these administrative regulations helped make a clearer description of Palestine in the Ottoman books. In fact, Kamus Ul-A'lâm, which was published in the late 19th century, describes the borders of Palestine as follows: ‘Its northern border is between Acre and Tiberia, extending southwards to Arîsh Castle. It is bounded by Beriyyetu'sh-Sham (Arabian Sahara) to the east and the Mediterranean Sea to the west, and its surface area is 30,000 km2. Palestine also includes the Governorship of Jerusalem, the provinces of Acre and Nablus of the Province of Beirut, and Hauran of the Province of Damascus.’ The Ottoman administration's denial of Herzl's request to grant the Jews a homeland in Acre and Haifa indicates that Palestine was home to the aforementioned districts from the perspective of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, this is clearer to see in a map published by the Ottoman 8th Army in 1915. Palestine is shown on the map as a geographical land that includes Jerusalem, Nablus, and Acre, and its northern borders on the map extend to the city of Sur and the Kazimiye (Litanî) river. The borders expanding as shown on the map include a significant portion of Beirut within the borders of Palestine. The details offered in Kamus al-A'lâm were probably influential in the drawing of this map. In addition, the Palestine Epistle, which was published during World War I, was printed in a way that harmonized with the borders of Europeans' holy sites, probably under the influence of German geographers. It seems a specific picture of Palestine was enshrined in the Ottoman imagination over time. However, the physical borders of the picture could not be put into effect. As it is clear to see, all these developments took place to counter the direct interventions of the Europeans in the Ottoman Empire and their views of annexing these lands out of the Ottoman Empire. Although the borders of Palestine established during the mandate, which was after the rule of the Ottoman Empire, generally coincide with the geographical description of Palestine in the final days of the Ottoman Empire, they are not thoroughly harmonious. The book, which is also the source of this text, is intended to uncover the version of Palestine in the Ottoman mind, whether it is situated within the borders of modern-day Palestine or not. Two methods were adopted to this end. Initially, the Tahrir (cadastral record) books kept in the early years of the Ottoman administration of Palestine (16th century) were analyzed and the sites such as sanjak, Kaza, nahiye, etc. were named. Then, the 19th-century sources were referred to. Of them, the administrative units in the Syrian Salnâme (Annual) of 1872, which points to the Ottoman administrative division in Syria, were unveiled. This offers readers a chance to compare the 16th century to the 19th century. Then, we referred to the Ottoman documents and various maps, confirming the aforementioned records and putting forth differences. Found out based on new sources, settlements are shown in tables. The atlas[1] that comes with the book shows a variety of maps drawn starting from the early years of Ottoman rule up to the year 1917. While the first and the final maps are Ottoman, not all of them were drawn by the Ottomans. However, what they had in common was that they all showed the land of Palestine under Ottoman rule. This study is not intended to set borders. It is intended to guide interested parties and history researchers and add to new studies to be carried out.

Source: Guideline and Atlas for the Vocabulary of Place Names in Ottoman Palestine

[1] Guideline and Atlas for the Vocabulary of Place Names in Ottoman Palestine